All articles

Exploring Multidimensional Data Structures To Improve Pattern Detection: With IBM Sr. Data & AI Architect

Saeed Kasmani, a Senior Data & AI Architect at IBM, explains how MIT’s latent-perception research reveals AI’s architectural security gaps.

Key Points

As organizations race to bolt on performance and security wrappers around powerful models, a new architecture-first approach is emerging to build AI that is both capable and safer by design.

Saeed Kasmani, a Senior Data & AI Architect at IBM, explains that MIT’s research on “latent perception” shows how today’s wrapper-based systems unlock impressive features yet leave core security gaps exposed.

By rebuilding models with built-in guardrails, awareness of their own internal state, and a multidimensional view of data, AI builders can deliver cheaper perception-like capabilities while reducing the risk of prompt-based attacks.

AI is like a living creature. Solve one problem, and it opens another door.

Recent MIT research shows how simple text prompts like "imagine seeing" and "imagine hearing" can make a language-only model behave as if it can "see" or "hear." But the real story is that the finding reveals a fundamental flaw in how many of today's AI systems are built and secured.

Instead of magically developing a sense of perception, the research on "latent perception" explains how AI navigates a hidden, multidimensional internal structure of data. Using the 'wrapper' method—backend systems that translate a user's plain language into a more effective prompt—can unlock multimodal-like benefits from simpler text models, which is a huge efficiency win. Yet this same approach is also how most AI security is currently implemented: as a superficial layer applied after the fact, rather than a feature integrated into its core.

The duality is something Saeed Kasmani, Ph.D., a Senior Data & AI Architect at IBM, understands all too well. With experience that spans research at institutions like CSIRO to high-stakes enterprise deployments at companies like Red Hat, Kasmani's work at the forefront of enterprise AI has given him a unique perspective. Today, his voice has become key in the debate over AI's architectural future.

According to Kasmani, the industry-wide rush for performance has created a generation of powerful yet fundamentally flawed systems. "AI is like a living creature. Solve one problem, and it opens another door," he says. "As soon as you walk into that new room, you are forced to confront a new issue to solve." For him, change is a permanent condition of technological progress—one that defies a single, final solution. In his view, the only effective path forward is to move beyond simple patches and toward a fundamental reinvention of LLMs from the ground up.

Beyond the benchmarks: A new model with self-awareness and safety built into its fundamental design is the solution, he says. "I think many top researchers are now thinking about how to reinvent the model to have built-in guardrails and a self-awareness of its own internal state. Putting that awareness into the model's architecture is what it means to reinvent the LLM from the beginning. Performance is not everything."

For Kasmani, the MIT research offers a blueprint for practical applications in scenarios like insurance claims and document processing. "We must see AI systems as multidimensional," Kasmani says. "When you do that, you can organize data more structurally and identify patterns that guide you to the right information. That is what's fascinating to me."

No new tricks: The discovery of this "multidimensional" internal space allows businesses to build backend "wrappers" that translate simple user queries into highly effective, sensory-cued prompts, Kasmani explains. "The end user shouldn't have to know these tricks. They will simply describe the problem in plain language, like pointing out where damage occurred on a car. Behind the scenes, the model we build should translate that raw text into a more effective prompt using a simple 'wrapper' that reshapes the input."

A cheaper sense: The approach could deliver major efficiency gains, allowing companies to achieve multimodal-like results without the expense of larger models. "This changes the cost, allowing organizations to avoid using huge multimodal models for some applications. They can simply craft a prompt that tells the model how to organize itself and show the desired output."

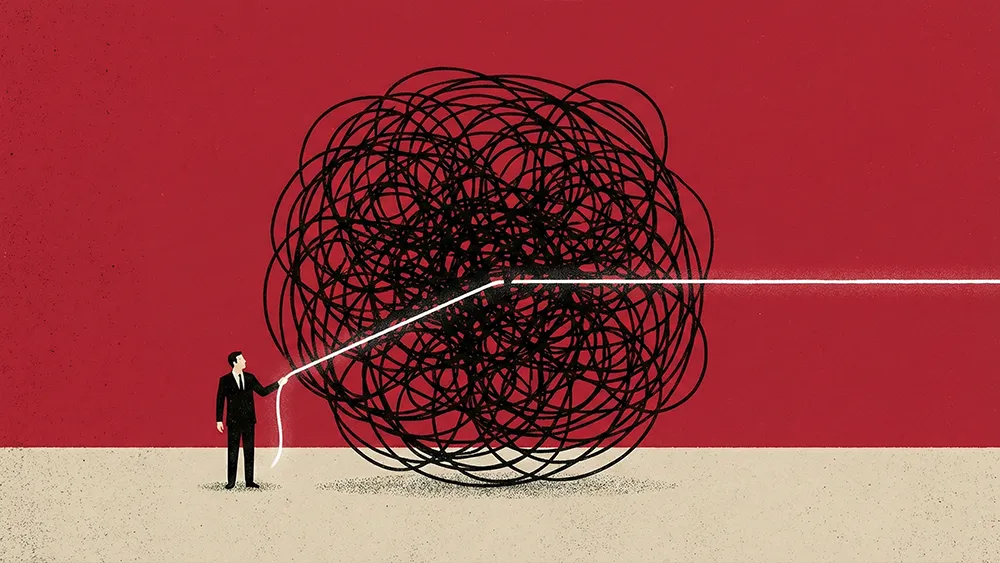

But here’s the paradox. That same "wrapper" concept, Kasmani explains, is also a core security vulnerability. From content filters to safety guardrails, nearly all current security measures are just wrappers.

Layers upon layers: For Kasmani, this is why the approach often falls short. "For one customer, we listed around 60 different AI-based attacks and provided five or six layers of security checks to mitigate them," he says. "Our finding was shocking: no matter how many layers you put on top of the model, there is always a chance you will miss an intrusion."

A hacker's handbook: Rather than embedded in its core design, the guardrails are merely superficial layers applied on top of the model, he continues. "Attackers can leverage this multi-dimensional concept to prompt a model to act as a hacker. We saw this recently when a group used Claude for an AI-based hack, without the techniques described in this new paper. If they had known about it, I can easily guess they could have defined even more sophisticated penetration tools."

The reason a clever prompt can bypass this "bolted-on" security isn't just a technical problem, Kasmani says. It's a philosophical one, best understood through a human metaphor: raising a child. "You cannot add a wrapper on your kids and make them 'nice kids.'"

Nature versus nurture: "If you teach your kids good behavior from the very beginning, especially the reason behind it, then when they are older, a bad influence will have a tough time infiltrating their mind. But if you leave a child without that training and then, at age 15, give them a list of rules, they are vulnerable."

The cycle of innovation doesn't just create new technical problems, however. It also reshapes how people work. Kasmani echoes a growing sentiment that AI's primary impact is likely to be the transformation, rather than the outright elimination, of jobs. But far from a blind techno-optimist, he is also quick to point out the human cost of this disruption. "Humans are intelligent beings, and they can readapt," he explains. "It will be challenging, and it could be very tough for people in their 50s or 60s. They don't have enough time to learn these new things. It could be very harsh for them."

Ultimately, this dual reality leaves Kasmani with a feeling familiar to many of those building our AI future: a mix of excitement for the potential and fear of the risks. "With every innovation I see in AI, my first reaction is happiness. I see how awesome it can be. But after a moment's thought, I'm a bit scared, because we need good people to take care of this technology properly," he concludes. "I am excited, but at the same time, I have some fear."