All articles

How Culture Clash Between Security and Compliance Puts Collaborative Defense at Risk

David Schwed, COO at SVRN, explains how compliance rules restrict intelligence sharing and why a new approach to collaborative defense is needed.

Key Points

Internal legal and compliance rules are preventing security experts from quickly sharing threat intelligence with their peers.

According to SVRN COO David Schwed, the issue is a culture of risk aversion and bureaucracy, not a lack of technical solutions.

By using AI and other privacy-enhancing technologies, organizations can share crucial security insights without exposing the sensitive data itself.

The security community shares information constantly. Before a threat even hits the public, security leaders are already alerting their peers about what to look out for. It's all done for the benefit of the community.

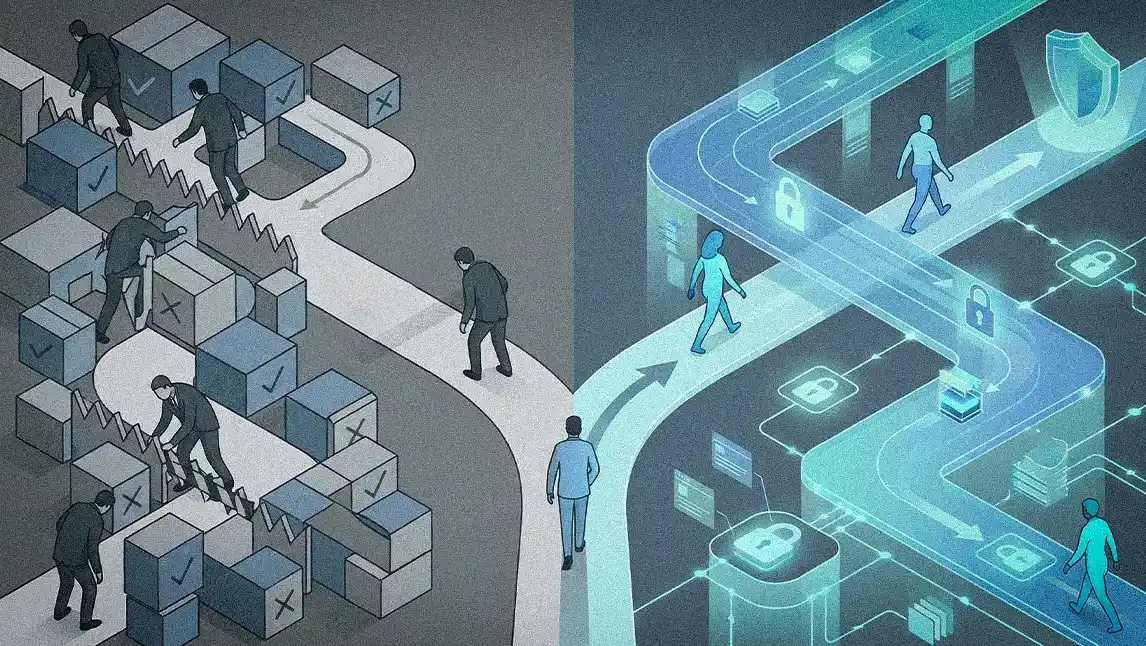

Business leaders have yet another threat to contend with—and it's coming from inside the organization. Instead of weak passwords or phishing, however, this insider threat manifests as legal and compliance frameworks. Now, the very policies put in place to protect enterprise systems from risks could be introducing entirely new ones. By limiting the security community's ability to share threat intelligence quickly, the fear of liability is weakening a historically strong culture of collaboration.

For a deeper understanding of shared intelligence, we spoke with David Schwed, J.D., Chief Operating Officer at SVRN, a company building the future of private, verifiable, user-owned AI. With experience serving in both C-level roles at firms such as Robinhood, BNY Mellon, and Galaxy Digital, and as the founding director of the Cybersecurity Master's Program at the Katz School of Science and Health, Schwed has built a career at the intersection of technology, finance, and law. From his perspective, the industry’s biggest challenges are cultural, not technical.

"The security community shares information constantly. Before a threat even hits the public, security leaders are already alerting their peers about what to look out for," Schwed says. "It's all done for the benefit of the community." But when official channels prove too slow, he continues, informal intelligence-sharing networks tend to emerge.

As a member of numerous Signal and Telegram groups with other CSOs and security heads, Schwed can attest to their growing necessity. Operating on encrypted platforms, these backchannels fill the gap left by concerns about liability, he explains.

- Watered-down warnings: The desire to collaborate is strong among security practitioners, Schwed continues. But they are often held back by the very processes designed to enable them. "As a security individual, I want to share all this information to help my colleagues at other institutions. But then compliance, legal, and my chief privacy officer step in and forbid it. So, you end up with watered-down intelligence that has been reviewed and approved. By the time it gets to me, it might be three weeks stale, or it’s missing the key details I actually need to share."

- Paralyzed by process: For Schwed, the biggest barriers are complex and often circular approval processes. It just makes intelligence-sharing too slow to be useful, he explains. "I'll have information that I want to share, but I need seven sign-offs. Nobody wants to be the one to say it's okay, so it's always deferred to somebody else. One person might say they don't have a problem with it, only to immediately defer by telling me to check with someone else. You end up creating a world where I'm disincentivized from even trying to participate in these networks because it's too hard to contribute."

When asked about the single biggest bottleneck, Schwed didn't hesitate. "Honestly? I think it's the lawyers and regulators." In his experience, a fear of liability tends to confine the most sensitive intelligence to small, trusted circles.

- From speculation to liability: "If I'm looking at an identity I'm unsure about, it could be DPRK, or it could be a legitimate profile. If I share that information with only medium confidence, other platforms might start flagging or blocking that individual. If they can't execute a trade, you're creating liability. The 'under the table' sharing is for intelligence that is more speculative. It's the kind of thing based on a belief or a hunch, and it's kept amongst trusted counterparties in small groups where we all know each other, not 800 CSOs whom we don't know."

As a result of this institutional gridlock, valuable solutions stay trapped in data silos, Schwed explains. To illustrate how cross-industry collaboration might solve real-world problems, he provides a clear example. "If a financial services organization could get signals from social media platforms, for instance, to see that a new account was just created on X, then Meta, LinkedIn, we could synthesize that data to determine if this is a real person or a synthetic identity. That's a clear example of how information sharing across different parties can result in a safer experience for investors."

- Tech to the rescue: The irony for Schwed is that the technology to solve this trust and liability problem already exists. His vision for the future involves a federated model where data stays local while insights are shared globally. "We can solve this in two ways. You can use zero-knowledge proofs to compute against the underlying data and show a result without revealing the information itself. The other approach is to use a shared, trusted execution environment, where you can confidentially share data and verify that the computation was confidential. The underlying data can never leave the enclave."

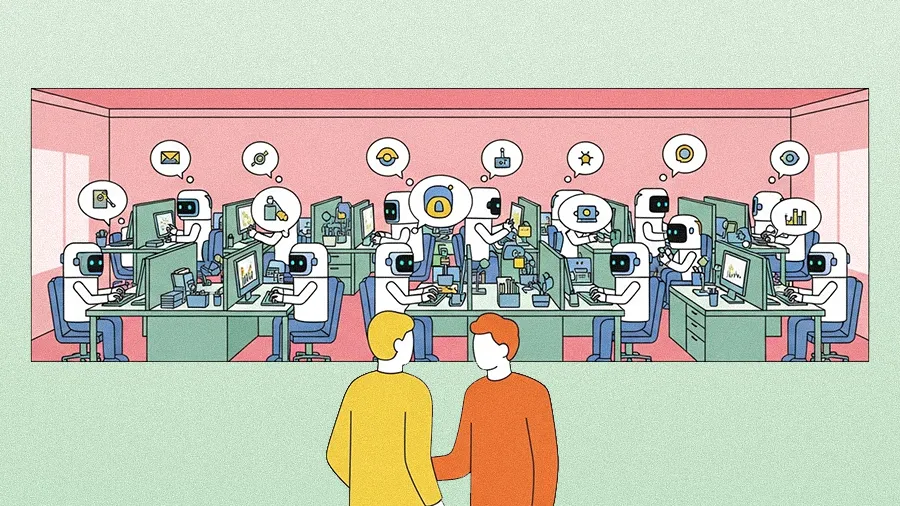

- Analyst to algorithm: But that kind of architecture relies on privacy-preserving computation, Schwed continues. "What's changed is AI. It allows us to synthesize all this information and create a generic 'AI analyst' that can apply a confidence level to the intelligence. In the past, I’d receive a bulletin, assign it to an analyst, and wait for them to synthesize it. Now, through orchestration, you can feed in all this threat intel and get a deterministic decision automatically."

Ultimately, Schwed's perspective helps close the loop. Turning the focus back to organizational education, he explains how, for many leaders, the future of collaborative defense depends on a new compliance mindset. Instead of focusing on "right versus wrong," reframe the conversation with regulators around a more transparent review of the decision-making process itself. "Create these environments, share the information, and when regulators come knocking, have a defensible position. That's all regulators and examiners care about," he concludes. "Their question isn't whether you were ultimately right or wrong, but how you got to your conclusion. They want to see that you thought through the process, understood the risk, and properly mitigated it."