AI at Scale in 2026

Data, Power, and Sovereignty Drive Infrastructure Strategy

Executive Summary

AI is everywhere, but infrastructure decides what’s possible.

Nearly every large enterprise is planning, preparing, or already adopting AI. Yet many leaders say their current environment cannot support AI quickly or safely enough.

The real constraints are data, power, and sovereignty.

AI projects most often fail because data is poor, fragmented, or inaccessible. At the same time, enterprises face rising energy costs, grid constraints, and geopolitical risk around where data lives and which laws apply.

Leaders who win treat AI as architecture.

The organizations pulling ahead are building unified data architectures across edge, core, and cloud; managing datasets rather than individual systems; designing for sovereignty and power from day one; and investing in governance and skills as seriously as in GPUs.

What AI & Data Looked Like in 2025…

Data isn’t an artifact of creating information. It’s the lifeblood of how businesses make decisions.

AI was embedded in everyday work.

In 2025, AI was embedded in everyday work.

- Executives used it daily to accelerate analysis, write and review code, summarize documents, and prototype ideas.

- Teams wove AI into forecasting models, cybersecurity workflows, document pipelines, and customer journeys.

- Agentic tools started to orchestrate tasks across multiple systems instead of just answering questions in a chat window.

An overwhelming majority of CIOs and IT decision-makers across the U.S., EMEA, and APJ said they were planning, preparing for, or already adopting AI. Nearly all said they see it as the most substantial opportunity to transform their organizations.

Tivo's Latest Video Trends Reveals Growing Consumer Interest in Video Services Bumdles Over Fragmented Streaming Experiences, Businesswire (October, 2025)

Organizations optimized existing systems first.

Nearly all organizations expected their first wave of AI to focus on optimizing existing systems rather than building entirely new ones. Leaders most often targeted AI at operational and customer-facing improvements before pursuing more speculative use cases.

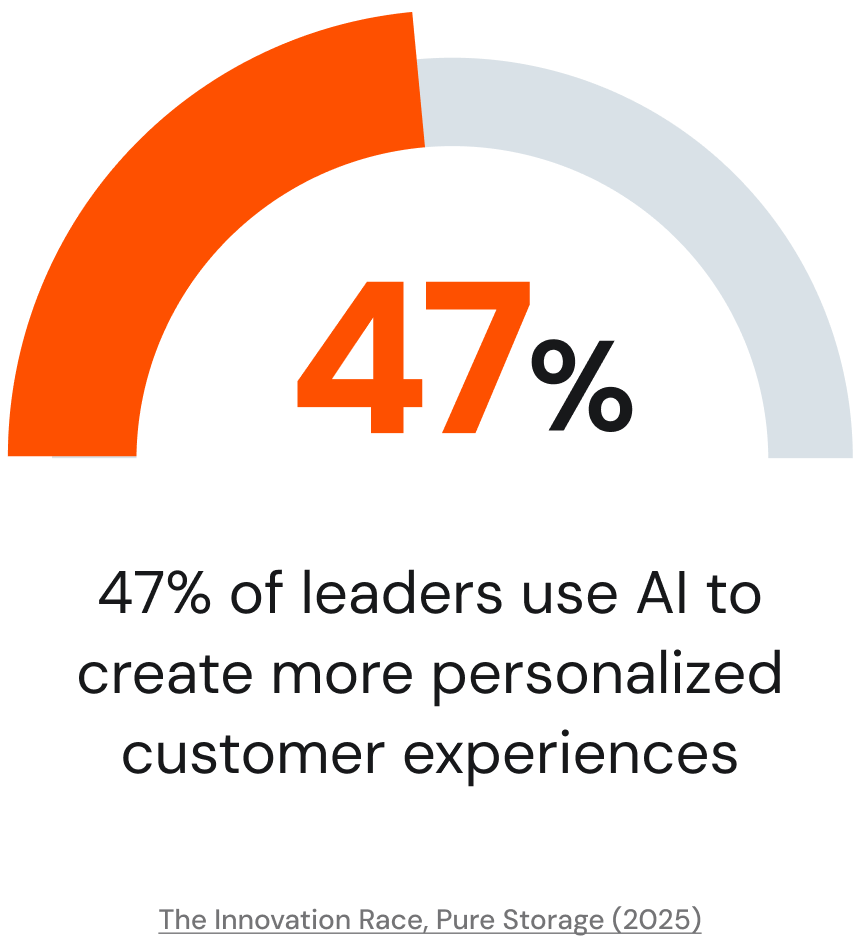

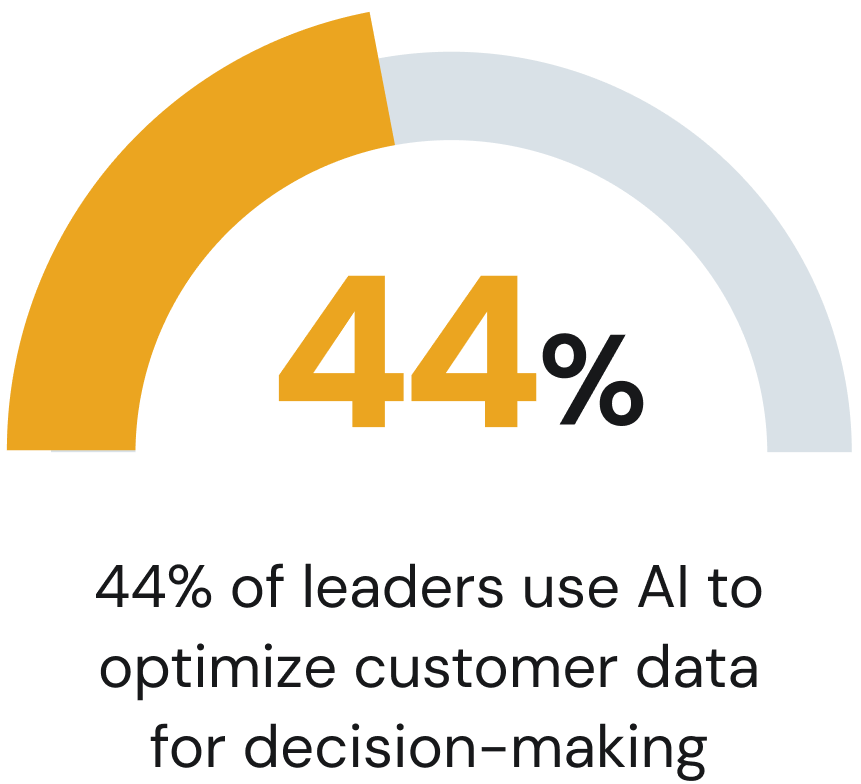

Leaders’ top AI priorities were efficiency gains and automation of repetitive tasks, more personalized customer experiences, and better use of customer data for decision-making.

Our most immediate value from AI comes from document processing, which cuts manual review time by around 70%.

How Leaders Use AI

.png)

Data and infrastructure determined which AI projects were successful.

The limits of AI have also become more apparent. Rather than the models themselves, most of those limits lie in the infrastructure and data underlying them.

Some projects moved from concept to production and delivered clear wins: defect rates fell, manual review times shrank, and response times in customer workflows improved. Others stalled—slowed by data quality issues, disjointed storage estates, governance and sovereignty concerns, and physical constraints like power, space, and grid capacity.

For data and infrastructure leaders, the central question in 2026 is whether their architecture can support AI reliably, safely, and sustainably over the next two to three years.

The better the data and the better your foundations, the better the output.

Legacy metrics don’t deliver value.

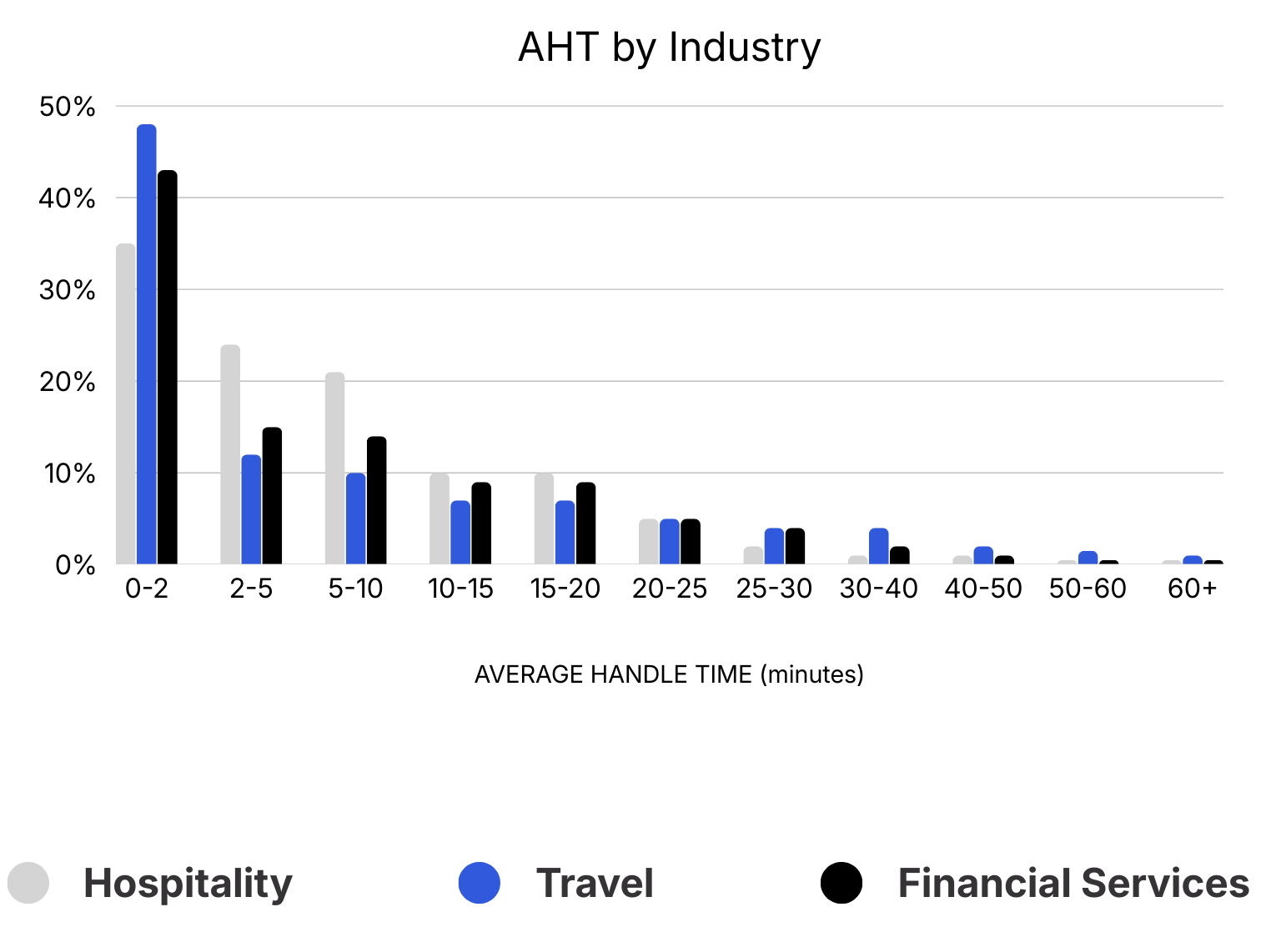

Fewer than 20% of AI-handled conversations reach successful resolution. In other words, most AI systems today assist with parts of the interaction, but still need humans to close the loop.

Why Driving Down Average Handle Time is Costing You Money, Cresta (2024).

Coaching patterns show a similar mismatch.

In most cases, increasing the number of coaching sessions does not reliably improve behavioral adherence. Because sessions aren't targeted at the specific behaviors driving outcomes, many teams spend more time in coaching meetings without seeing clear gains.

The value is still in the conversation with the customer. You need context and judgment to decide what actually matters.

Agentic AI is introducing risk.

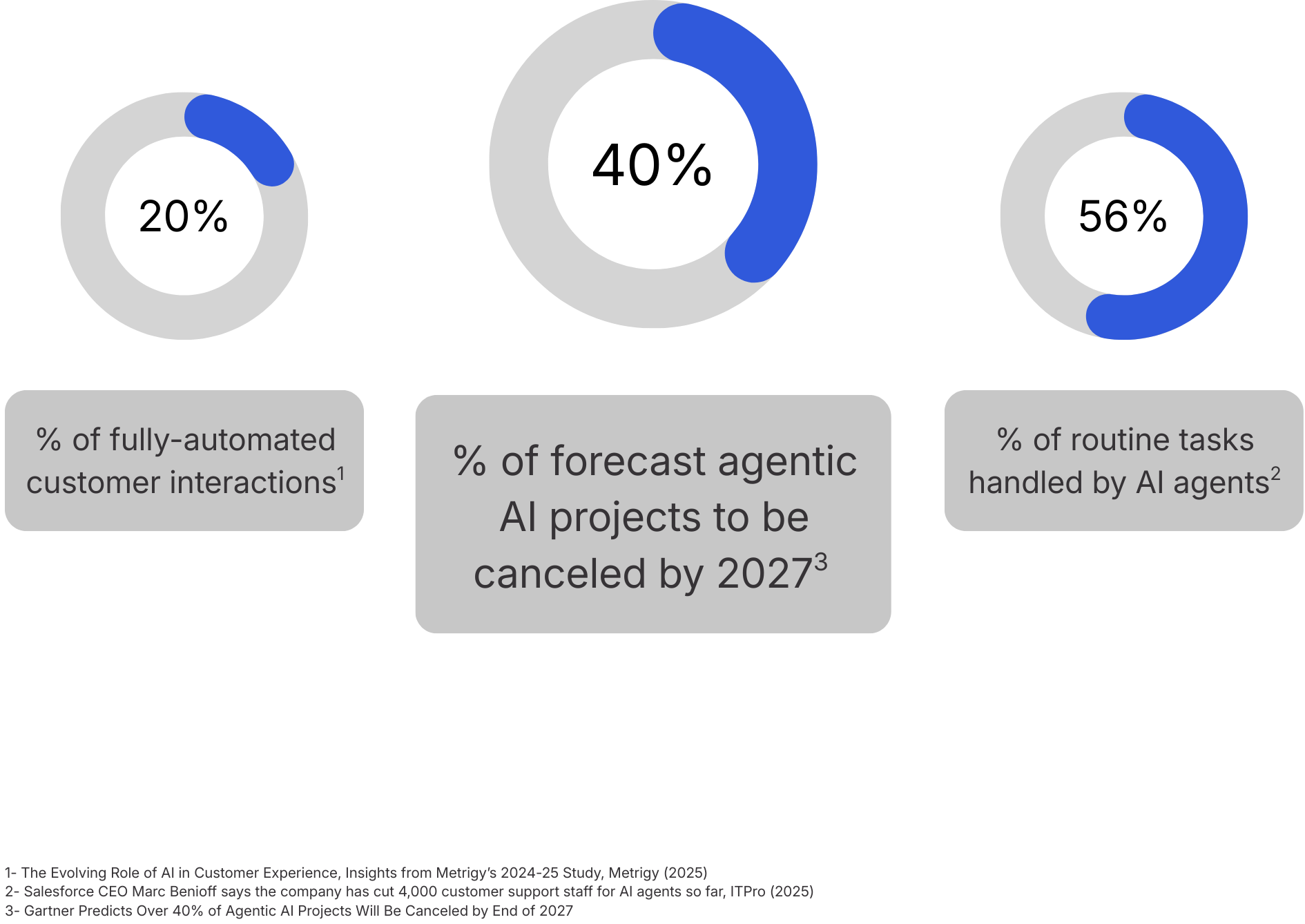

Agentic AI now behaves more like a junior employee than a script. AI is already fully automating around 20% of customer interactions for some organizations, with leaders expecting that share to rise.

In many small and mid-sized contact centers, executives report that AI agents now handle 30–60% of routine tasks, particularly in self-service and low-complexity workflows.

But adoption is still early, and the risk is real.

Gartner forecasts that more than 40% of agentic AI projects will be canceled by the end of 2027 due to escalating costs, unclear business value, or weak risk controls.

In banking, the key question is not just ‘does this work’ but ‘can we explain it.

If AI starts making suggestions without the right data or consent, we can lose trust that took years to build.

That combination of high ambition, high failure risk, and growing complexity shapes the landscape for 2026.

Leaders now have to treat agentic AI as part of the workforce and the operating model, not as a set of point solutions, and they need to set clear expectations for where AI will act independently and where humans must remain in the loop.

What’s New Entering 2026

We have to understand the underlying problems and bring tools–including AI–that the industry hasn’t had the time or perspective to explore.

AI is universal and centered on data-heavy workloads.

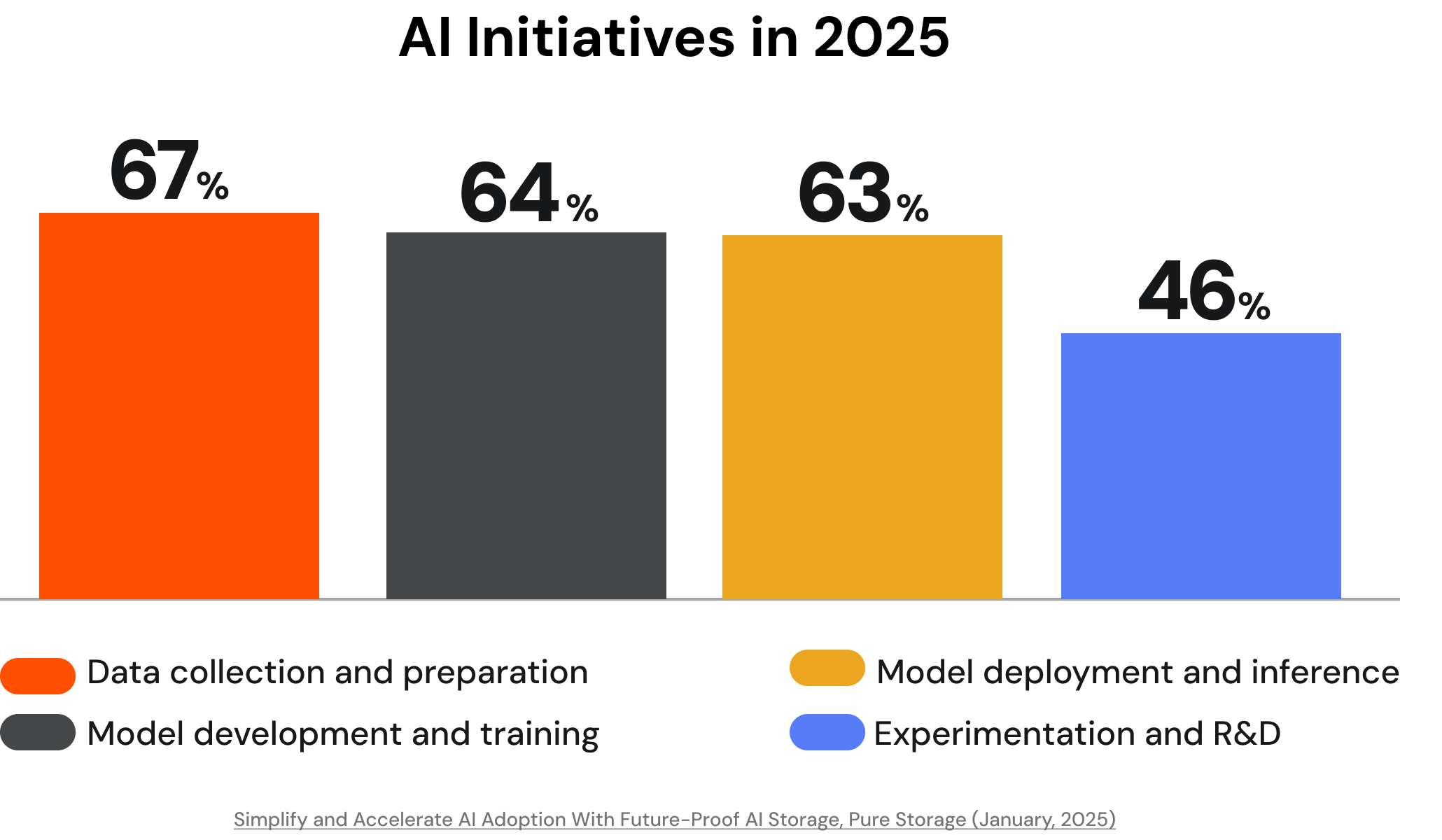

Today, nearly all organizations say they are planning, preparing for, or already adopting AI. At the same time, predictive and generative AI initiatives are already the number-one driver of new storage projects.

Leaders say their initiatives primarily support the full lifecycle of AI, from data ingestion through experimentation. Organizations are investing not only in GPU clusters and specialized compute, but in the data pipelines and storage systems that feed AI end-to-end.

MDM is the foundation that lets AI make better decisions—clean, standardized, governed data is what prevents AI hallucinations from becoming business decisions.

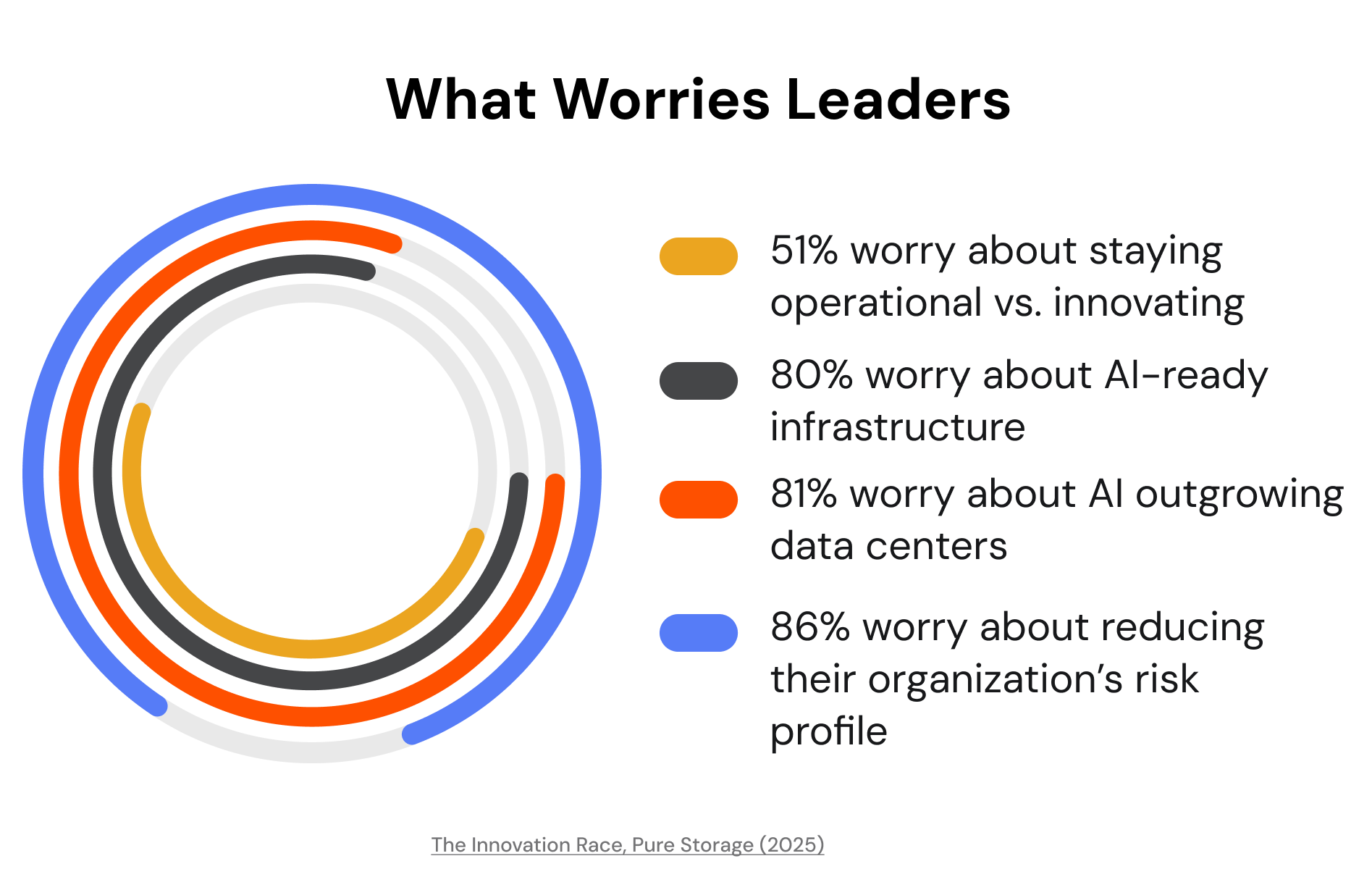

Infrastructure anxiety is widespread.

As AI demand grows, infrastructure no longer feels like a neutral backdrop. Leaders express a consistent fear that it will hold them back, especially as AI projects scale beyond pilots.

Most worry their business will be left behind if their infrastructure cannot support AI fast enough, believing AI-generated data is likely to outgrow their current data centers. Even more say reducing their organization’s risk profile is their top priority, and all but some believe the budget they spend mitigating cyberthreats would be better spent on innovation. Now, more than half say they spend most of their time “keeping the lights on” rather than innovating.

In this environment, data infrastructure feels less like a neutral platform and more like a constraint—caught between regulatory expectations on one side and AI-powered competitors on the other.

Tivo's Latest Video Trends Reveals Growing Consumer Interest in Video Services Bumdles Over Fragmented Streaming Experiences, Businesswire (October, 2025)

AI agents have stopped being skunkworks in the garage and are now becoming integral to how organizations run.

“AI is already reducing about 30–40% of software issues before ever reaching our vehicles.

AI failures are a data problem.

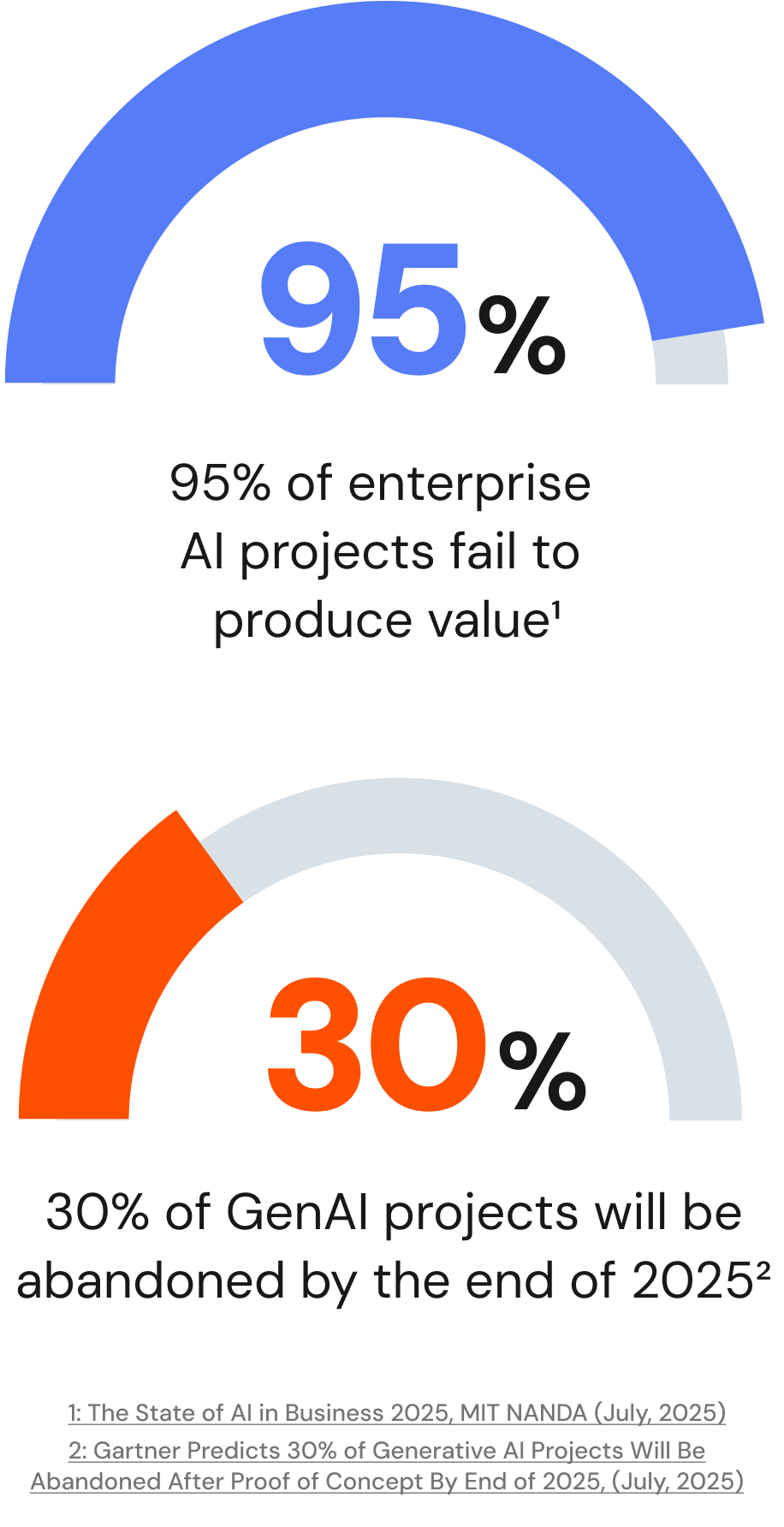

Even as investment accelerates, AI’s success rate remains low. Many organizations find that the hardest problems are not model selection or GPU capacity, but how data is captured, governed, and made available to AI systems and teams.

Almost all enterprise AI projects fail to reach durable, scaled value, and almost one-third of generative AI projects are forecast to be abandoned after proof of concept by the end of 2025, most often due to poor data quality.

Other signals highlight the human side. In one corporate AI training program, around 20,000 participants started, but only 3,000 completed—roughly a 15% completion rate. These patterns reflect deeper issues in how data is captured, governed, and made available—not only in the choice of model.

At the same time, when infrastructure and data are ready, outcomes improve. For example, financial institutions deploying AI data platforms for fraud detection can see a 40–60% reduction in false positives compared with traditional rule-based systems.

You have to assume more actors—human, system, and agent—will touch your data.

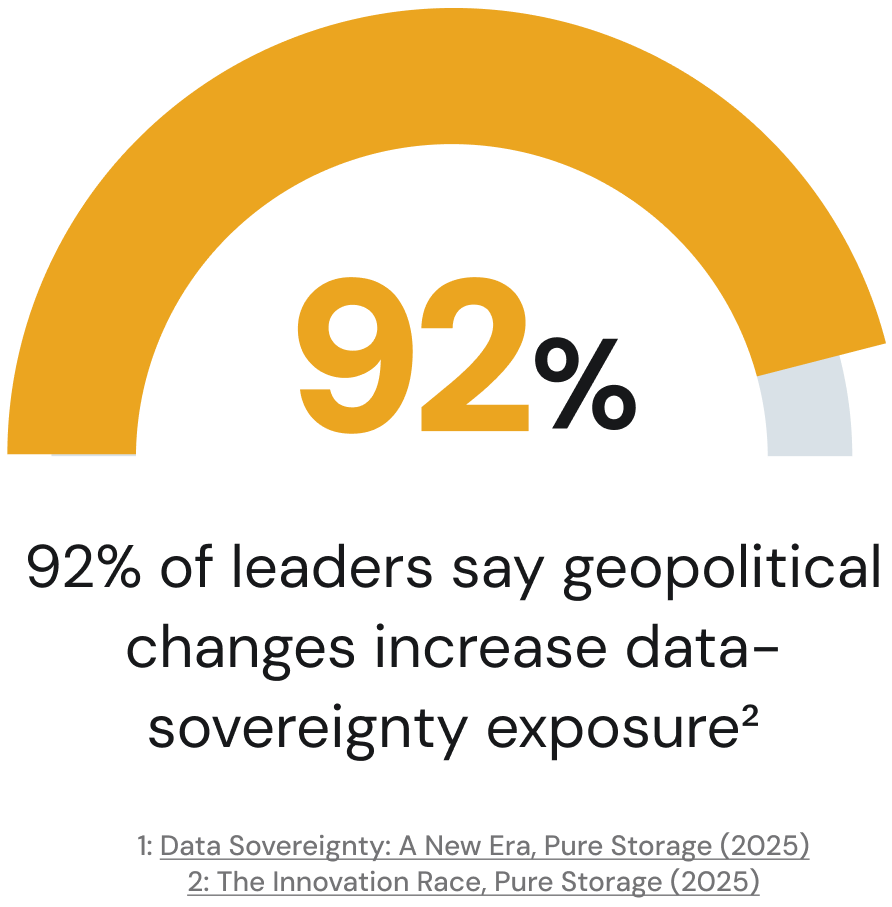

Sovereignty and geopolitics took center stage.

Data sovereignty has become a board-level concern. Rather than treating sovereignty as a narrow compliance checkbox, organizations now weave it into architecture decisions: which workloads run where, which providers they use, and how data moves across borders.

All business leaders are reassessing their data location strategies due to sovereignty risks, most say geopolitical changes increase their data-sovereignty exposure, and more than three-quarters have already integrated sovereignty into business strategy through multi-cloud models, sovereign data centers, or contractual governance clauses.

How Leaders View Data Sovereignty

.png)

AI in finance is about control, ownership, and sovereignty over the data and infrastructure you’re operating on.

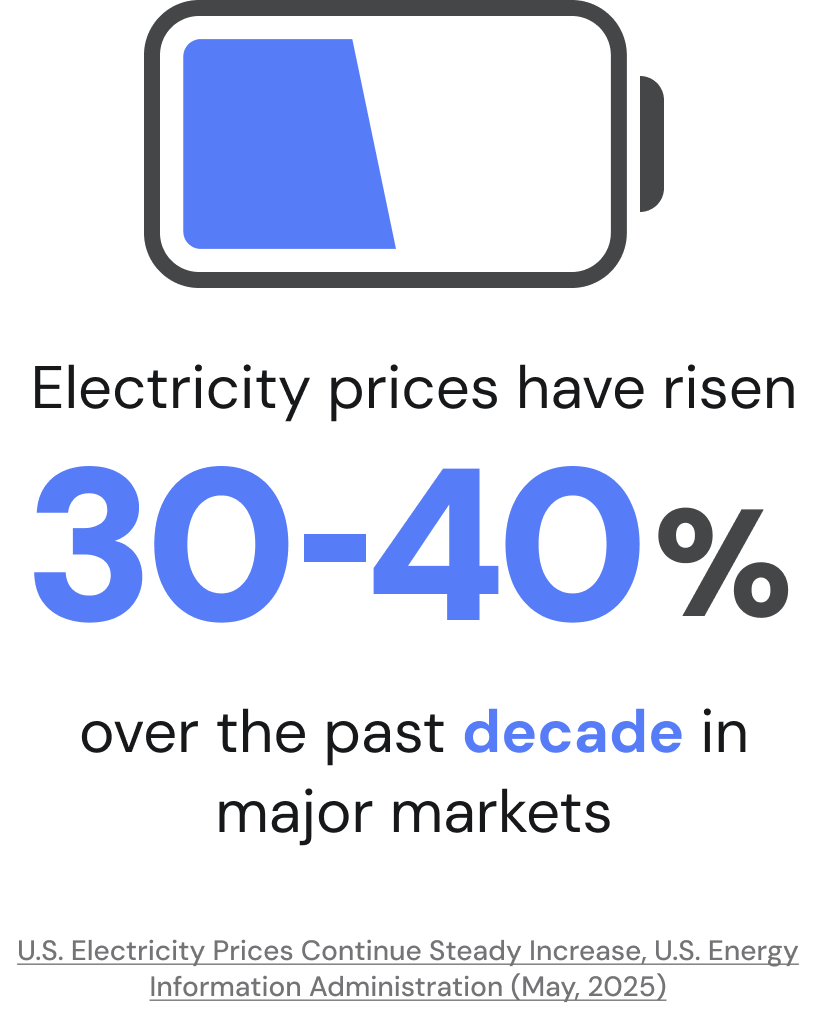

Power and physical limits are emerging.

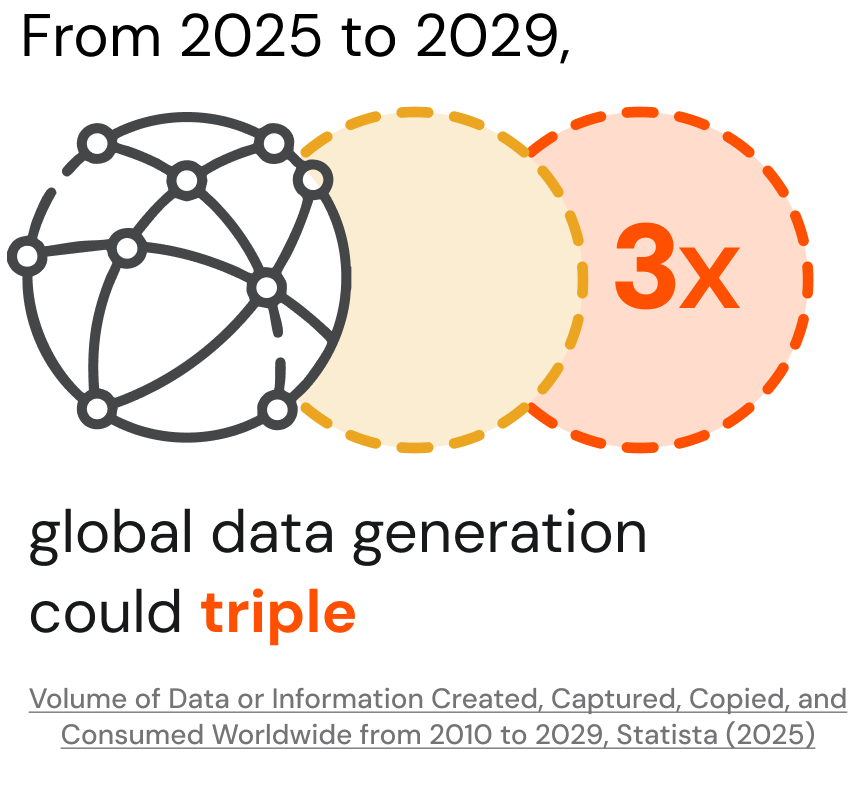

Finally, AI adoption is colliding with physical reality. Data and infrastructure leaders must now contend with rising power costs, constrained grids, and unprecedented data volumes generated by applications and sensors.

Electricity prices in major markets have risen significantly over the past decade. More recently, some cities have publicly stated that they can no longer support new data centers due to power limitations.

Hyperscalers are signing custom contracts with nuclear facilities—including efforts to restart sites such as Three Mile Island—to secure dedicated energy for AI workloads.

A large enterprise can generate more than 22 terabytes of data per day, and a single advanced sensor array can add around 100 terabytes per day on top of that, with organizations already receiving data “in the hundreds of terabytes daily—soon to be petabytes.”

For data and infrastructure leaders, these realities—data volume, sovereignty, and power—have become first-order constraints. They shape what is possible with AI, regardless of how advanced the models become.

Scalability is now table stakes. The harder problem is making data architectures intuitive.

How AI is Rewiring Data and Infrastructure

Most organizations have important data scattered across disparate silos. AI is forcing that conversation in a way nothing else has.

From storage management to dataset management.

For decades, infrastructure teams focused on provisioning and managing storage systems—arrays, volumes, file systems, and buckets. AI has shifted the unit of work to datasets.

Now, organizations need to identify which datasets feed which AI models and applications, understand the lineage, quality, and policies associated with each dataset, and manage versions, copies, and placements across edge, core, and cloud.

A growing share of storage and HCI initiatives explicitly support data collection, preparation, training, and inference. Now, AI value depends on how datasets are managed, not just where they sit.

In bioinformatics, we spend a lot of time as data janitors—cleaning metadata, merging messy spreadsheets, and making sure the samples even match.

The old idea of a single ‘source of truth’ is evolving into a semantic layer.

From monolithic truth to semantic and federated models.

The traditional goal of “one enterprise data warehouse” or “one MDM to rule them all” has given way to a more nuanced reality. Global organizations operate across multiple regions, each with its own regulations, systems, and needs.

Rather than forcing everything into one repository, leaders now talk about semantic layers that unify business definitions across systems, federated data models that allow domains and regions to own their data while aligning on shared structures, and master and reference data that act as connective tissue between applications and analytics.

These models support both global consistency and local autonomy by supporting region-specific sovereignty requirements without multiplying chaos.

From ‘cloud vs. data center’ to hybrid-by-design.

The first wave of cloud adoption often revolved around an either/or decision: move everything, or keep everything. AI workloads have made that framing obsolete.

Most AI programs now span on-premises clusters in existing data centers, cloud-based GPU fleets and managed AI services, and edge environments closer to data sources and users

Data and infrastructure leaders increasingly adopt an “and” strategy that covers on-premises for sovereignty-sensitive, latency-critical, or high-utilization workloads; cloud for elasticity, experimentation, and global reach; and edge for data gravity and low-latency inference.

Instead of simply lifting and shifting workloads, teams refactor applications and data flows so they can be managed consistently across environments.

Cloud not done the cloud way is usually more expensive than staying on-prem.

Token cost and context engineering are not afterthoughts. They’re design constraints.

From ignoring challenges to designing around them.

Power and sovereignty have moved from background concerns to core design inputs. The rise in energy prices, grid limitations, and ESG expectations has pushed leaders to measure power consumption per unit of data processed and per model trained, space efficiency per rack and per data center, and carbon impact of different placement decisions (on-prem, edge, cloud regions).

At the same time, sovereignty considerations mean not every AI workload can run everywhere. Leaders now plan which datasets can move across borders, and which must remain local, how to deploy models to sovereign clouds or on-premises clusters when needed, and how to architect for future regulatory changes without freezing innovation.

These pressures have driven interest in denser, more efficient storage and in unified control planes that can automatically apply placement and protection policies.

Playbook for AI & Data Leaders:

5 Steps to Take in 2026

1

1. Inventory and rationalize AI datasets.

Start by getting clear on the data that matters most. Most AI initiatives rely on a surprisingly small set of critical datasets: core customer records, transaction logs, telemetry streams, content repositories, and a handful of reference tables. Yet those datasets often exist in multiple versions and locations.

List the 10–20 datasets most critical to current and planned AI initiatives.

Map where they live today—edge, data center, multiple clouds—and how many copies exist.

Assign clear ownership for each dataset’s definition, quality, and policies.

Consolidate redundant or unknown copies and establish a simple standard for “AI-ready” datasets (schema stability, freshness, and basic quality thresholds).

1

2. Build a unified data control plane.

Managing datasets one system at a time does not scale in a hybrid AI world. A unified control plane lets teams define and enforce policies once, then apply them automatically wherever data lives. The goal is simple: move away from ad hoc scripts and manual configuration toward consistent, policy-based control.

Choose or extend a platform that can sit above individual storage systems.

Express core policies in machine-readable form.

Use automation to enforce lifecycle, backup, and placement policies across data centers, cloud, and edge locations.

1

3. Design for sovereignty and power.

Sovereignty and power are now fundamental planning inputs, not edge cases. Rather than treating them as issues to handle at the end, leading organizations bring them into early design and capacity planning. A simple way to start is with a combined sovereignty and power “heat map.”

Overlay workload locations with applicable data regulations, power prices, and grid capacity.

Classify workloads as sovereignty-critical, latency-critical, power-sensitive, or flexible.

Use these classifications to guide placement decisions for new AI workloads.

1

4. Tie AI infrastructure to clear, measurable outcomes.

Infrastructure-only goals are rarely compelling. What resonates in the boardroom is how AI changes outcomes. For each major AI initiative, leaders can ask three simple questions: What problem are we solving, and for whom? How will we know it worked—and within what timeframe? Which specific data and infrastructure capabilities are required to support that outcome?

Define a small set of KPIs that matter: defect rate, cycle time, review hours, cash conversion, and energy per workload.

Make sure the enabling datasets and infrastructure patterns are explicit, not assumed.

Pilot with a limited scope, measure, and only then expand.

1

5. Invest in people, governance, and skills.

AI value depends as much on people and process as on hardware. Most organizations now recognize that:

Governance and security models have to account for new actors—humans, systems, and agents—and engineers and operators need a working understanding of AI workload patterns, observability needs, and data governance. Because AI touches infrastructure, data, security, risk, and business outcomes, cross-functional decision-making is now essential.

Establish regular forums where infrastructure, data, security, and business leaders review AI usage, incidents, and infrastructure needs together.

Fold AI-ready data and AI governance into existing transformation programs instead of treating them as side projects.

Design role-specific training for mid-level engineers, SREs, and analysts on how AI workloads behave, what they require from storage and networks, and how to keep them compliant and resilient.

AI & Data Checklist for 2026

Use these questions below to pressure-test your current plans. If any of these answers are unclear or negative, those are natural starting points for 2026 planning.

Do we have a clear inventory of the key datasets that power our AI initiatives, including owners, locations, and policies?

Can we manage dataset lifecycle, protection, and placement through a unified control plane across data center, cloud, and edge?

Have we mapped sovereignty and power constraints to our AI workload placement decisions, rather than discovering them late?

For each major AI project, have we defined specific business outcomes and metrics—and linked them explicitly to data and infrastructure capabilities?

Are our governance and security models designed for AI-era actors—humans, systems, and agents—with Zero Trust applied to data flows, not just networks?

Are our governance and security models designed for AI-era actors—humans, systems, and agents—with Zero Trust applied to data flows, not just networks?

Do our training and literacy programs reach the engineers and operators who will keep AI workloads running, not only data scientists and executives?

Is there a cross-functional group (data, infra, security, risk, business) that meets regularly to review AI usage, incidents, and infrastructure needs?

When we look at AI project failures or delays, how often do root causes trace back to data or infrastructure—and what are we doing about it?

Where Data & Infrastructure Leaders Go Next

AI has moved from novelty to necessity. Nearly every organization now has some combination of copilots, agents, and AI-augmented services woven into its operations. The real question is no longer “if” or even “when,” but “on what foundation.” That foundation is data and infrastructure.

Leaders who treat AI as primarily a modeling problem will continue to experience stalled projects, unexpected costs, and governance headaches. Those who recognize AI as an architectural challenge—spanning datasets, control planes, sovereignty, power, and people—will be better equipped to navigate the next two to three years.

Signals from the Field

Methodology

This editorial report draws on a mix of qualitative and quantitative inputs to reflect a reality already visible to data and infrastructure leaders.

First, we synthesized findings from Pure Storage research programs, including global surveys of CIOs and IT decision-makers on AI adoption, infrastructure readiness, risk, and innovation tradeoffs. These sources provided the quantitative backbone of the report, including statistics on AI adoption, infrastructure concerns, data sovereignty, and AI-driven storage projects.

Second, we conducted interviews with executives and practitioners across sectors: automotive, financial services, healthcare, consulting, cybersecurity, and technology, including senior leaders such as CIOs, heads of AI/ML, enterprise architects, infrastructure leaders, and consultants working at or with large enterprises. Many of these conversations also inform standalone feature stories in trade publications.

Finally, the editorial team compared themes across research data and interview transcripts to identify where AI is already delivering value, and where it is failing; how data, infrastructure, sovereignty, and power constraints show up in practice; what leading organizations are doing differently in their architectures, governance, and operating models. The result is a 360-degree snapshot of AI data infrastructure in 2025–2026 and a practical stance on what leaders can do next to ensure their architecture decides in their favor.